Sher Shah’s Work

Sher Shah was one of the most distinguished rulers of north India who had done a number of developmental works (along with well-planned administrative works). His works can be studied under the following heads:

Administrative Works

Sher Shah re-established law and order across the length and breadth of his empire.

Sher Shah placed considerable emphasis on justice, as he used to say, “Justice is the most excellent of religious rites, and it is approved alike by the king of infidels and of the faithful“.

Sher Shah did not spare oppressors whether they were high nobles, men of his own tribe or near relations.

Qazis were appointed at different places for justice, but as before, the village panchayats and zamindars also dealt with civil and criminal cases at the local level.

Sher Shah dealt strictly with robbers and dacoits.

Sher Shah was very strict with zamindars who refused to pay land revenue or disobeyed the orders of the government.

Administrative Division

A number of villages comprised a pargana. The pargana was under the charge of the shiqdar, who looked after law and order and general administration, and the munsif or amil looked after the collection of Land revenue.

Above the pargana, there was the shiq or sarkar under the charge of the shiqdar-i-shiqdran and a munsif-i-munsifan.

Accounts were maintained both in the Persian and the local

languages (Hindavi).

Sher Shah apparently continued the central machinery of administration, which had been developed during the Sultanate period. Most likely, Sher Shah did not favor leaving too much authority in the hands of ministers.

Sher Shah worked exceptionally hard, devoting himself to the affairs of the state from early morning to late at night. He also toured the country regularly to know the condition of the people.

Sher Shah’s excessive centralization of authority, in his hands, has later become a source of weakness, and its harmful effects became apparent when a masterful sovereign (like him) ceased to sit on the throne.

The produce of land was no longer to be based on the guess work, or by dividing the crops in the fields, or on the threshing floor rather Sher Shah insisted on measurement of the sown land.

Schedule of rates (called ray) was drawn up, laying down the state’s share of the different types of crops. This could then be converted into cash on the basis of the prevailing market rates in different areas. Normally, the share of the state was one-third of the produce.

Sher Shah’s measurement system let peasants to know how much they had to pay to the state only after sowing the crops.

The extent of area sown, the type of crops cultivated, and the amount each peasant had to pay was written down on a paper called patta and each peasant was informed of it.

No one was permitted to charge from the peasants anything extra. The rates which the members of the measuring party were to get for their work were laid down.

In order to guard against famine and other natural calamities, a cess at the rate of two and half seers per bigha was also levied.

Sher Shah was very solicitous for the welfare of the peasantry, as he used to say, “The cultivators are blameless, they submit to those in power, and if I oppress them they will abandon their villages, and the country will be ruined and deserted, and it will be a long time before it again becomes prosperous“.

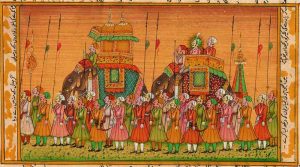

Sher Shah developed a strong army in order to administer his vast empire. He dispensed with tribal levies under tribal chiefs, and recruited soldiers directly after verifying their character.

The strength of Sher Shah’s personal army was recorded as:

o 150,000 cavalry;

o 25,000 infantry armed with matchlocks or bows;

o 5,000 elephants; and

o A park of artillery.

Sher Shah set up cantonments in different parts of his empire; besides, a strong garrison was posted in each of them.

Sher Shah also developed a new city on the bank of the Yamuna River near Delhi. The sole survivor of this city is the Old Fort (Purana Qila) and the fine mosque within it.

One of the finest nobles, Malik Muhammad Jaisi (who had written Padmavat in Hindi) was the patron of Sher Shah’s reign.

Akbar’s Administrative System

Though Akbar adopted Sher Shah’s administrative system, he did not find it that much beneficial hence he had started his own administrative system.

In 1573, just after returning from Gujarat expedition, Akbar paid personal attention to the land revenue system. Officials called as ‘karoris’ were appointed throughout the north India. Karoris were responsible for the collection of a crore of dams (i.e. Rs. 250,000).

In 1580, Akbar instituted a new system called the dahsala; under this system, the average produce of different crops along with the average prices prevailing over the last ten (dah) years were calculated. However, the state demand was stated in cash. This was done by converting the state share into money on the basis of a schedule of average prices over the past ten years.

Akbar introduced a new land measurement system (known as the zabti system) covering from Lahore to Allahabad, including Malwa and Gujarat.

Under the zabti system, the shown area was measured by means of the bamboos attached with iron rings.

The zabti system, originally, is associated with Raja Todar Mal (one of the nobles of Akbar), therefore, sometimes, it is called as Todar Mal’s bandobast.

Todar Mal was a brilliant revenue officer of his time. He first served on Sher Shah’s court, but later joined Akbar.

Besides zabti system, a number of other systems of assessment were also introduced by Akbar. The most common and, perhaps the oldest one was ‘batai’ or ‘ghalla-bakshi.’

Under batai system, the produce was divided between the peasants and the state in a fixed proportion.

The peasants were allowed to choose between zabti and batai under certain conditions. However, such a choice was given when the crops had been ruined by natural calamity.

Under batai system, the peasants were given the choice of paying in cash or in kind, though the state preferred cash.

In the case of crops such as cotton, indigo, oil-seeds, sugarcane, etc., the state demand was customarily in cash. Therefore, these crops were called as cash-crops.

The third type of system, which was widely used (particularly in Bengal) in Akbar’s time was nasaq.

Most likely (but not confirmed), under the nasaq system, a rough calculation was made on the basis of the past revenue receipts paid by the peasants. This system required no actual measurement, however, the area was ascertained from the records.

The land which remained under cultivation almost every year was called ‘polaj.’

When the land left uncultivated, it was called ‘parati’ (fallow). Cess on Parati land was at the full (polaj) rate when it was cultivated.

The land which had been fallow for two to three years was called ‘chachar,’ and if longer than that, it was known as ‘banjar.’

The land was also classified as good, middling, and bad. Though one-third of the average produce was the state demand, it varied according to the productivity of the land, the method of assessment, etc.

Akbar was deeply interested in the development and extension of cultivation; therefore, he offered taccavi (loans) to the peasants for seeds, equipment, animals, etc. Akbar made policy to recover the loans in easy installments.

Army

Akbar organized and strengthened his army and encouraged the mansabdari system. “Mansab” is an Arabic word, which means ‘rank’ or ‘position.’

Under the mansabdari system, every officer was assigned a rank (mansab). The lowest rank was 10, and the highest was 5,000 for the nobles; however, towards the end of the reign, it was raised to 7,000. Princes of the blood received higher mansabs.

The mansabs (ranks) were categorized as:

o Zat

o Sawar

The word ‘zat’ means personal. It fixed the personal status of a person, and also his salary.

The ‘sawar’ rank indicated the number of cavalrymen (sawars) a person was required to maintain.

Out of his personal pay, the mansabdar was expected to maintain a corps of elephants, camels, mules, and carts, which were necessary for the transport of the army.

The Mughal mansabdars were paid very handsomely; in fact, their salaries were probably the highest in the world at the time.

A mansabdar, holding the rank of:

o 100 zat, received a monthly salary of Rs. 500/month;

o 1,000 zat received Rs. 4,400/month;

o 5,000 zat received Rs. 30,000/month.

During the Mughal period, there was as such no income tax.

Apart from cavalrymen, bowmen, musketeers (bandukchi), sappers, and miners were also recruited in the contingents.

Administrative Units

Akbar followed the system of the Subhah, the pargana, and the sarkar as his major administrative units.

Subhah was the top most administrative unit, which was further sub-divided into Sarkar. Sarkar (equivalent to district) was constituted of certain number of parganas and pargana was the collective administrative unit of a few villages.

The chief officer of subhah was subedar.

The chief officers of the sarkar were the faujdar and the amalguzar.

The faujdar was in-charge of law and order, and the amalguzar was responsible for the assessment and collection of the land revenue.

The territories of the empire were classified into jagir, khalsa and inam. Income from khalsa villages went directly to the royal exchequer.

The Inam lands were those property, which were given to learned and religious men.

The Jagir lands were allotted to the nobles and members of the Royal family including the queens.

The Amalguzar was assigned to exercise a general supervision over all types of lands for the purpose of imperial rules and regulations and the assessment and collection of land revenue uniformly.

Akbar reorganized the central machinery of administration on the basis of the division of power among various departments.

During the Sultanate period, the role of wazir,

the chief adviser of the ruler, was very important, but Akbar reduced the responsibilities of wazir by creating separate departments.

Akbar assigned wazir as head of the revenue department. Thus, he was no longer the principal adviser to the ruler, but an expert in revenue affairs (only). However, to emphasize on wazir’s importance, Akbar generally used the title of diwan or diwan-i-ala (in preference to the title wazir).

The diwan was held responsible for all income and expenditure, and held control over khalisa, jagir and inam lands.

The head of the military department was known as the mir bakhshi. It was the mir bakhshi (and not the diwan) who was considered as the head of the nobility.

Recommendations for the appointments to mansabs or for the promotions, etc., were made to the emperor through the mir bakhshi.

The mir bakhshi was also the head of the intelligence and information agencies of the empire. Intelligence officers and news reporters (waqia-navis) were posted in all regions of the empire and their reports were presented to the emperor’s court through the mir bakhshi.

The mir saman was the third important officer of Mughal Empire. He was in-charge of the imperial household, including the supply of all the provisions and articles for the use of the inmates of the harem or the female apartments.

The judicial department was headed by the chief qazi. This post was sometimes clubbed with that of the chief sadr who was responsible for all charitable and religious endowments.

To make himself accessible to the people as well as to the ministers, Akbar judiciously divided his time. The day started with the emperor’s appearance at the jharoka of the palace where large numbers of people used to assemble daily to have a glimpse of the ruler, and to present petitions to him if required so.

Akbar’s Provinces

In 1580, Akbar classified his empire into twelve subas (provinces) namely:

o Bengal

o Bihar

o Allahabad

o Awadh

o Agra

o Delhi

o Lahore

o Multan

o Kabul

o Ajmer

o Malwa and

o Gujarat

Each of these subah consisted of a governor (subadar), a diwan, a bakhshi, a sadr, a qazi, and a waqia-navis.

Final Destination for Kerala PSC Notes and Tests, Exclusive coverage of KPSC Prelims and Mains Syllabus, Dedicated Staff and guidence for KPSC Kerala PSC Notes brings Prelims and Mains programs for Kerala PSC Prelims and Kerala PSC Mains Exam preparation. Various Programs initiated by Kerala PSC Notes are as follows:-

- Kerala PSC Mains Tests and Notes Program 2025

- Kerala PSC Prelims Exam 2025- Test Series and Notes Program

- Kerala PSC Prelims and Mains Tests Series and Notes Program 2025

- Kerala PSC Detailed Complete Prelims Notes 2025